| BOOKS | F. A. Q. | ARTICLES | TALKS | ABOUT KEN | DONATE | BEYOND OUR KEN |

|---|

By Ken Croswell

Published on ScienceNOW (May 24, 2012)

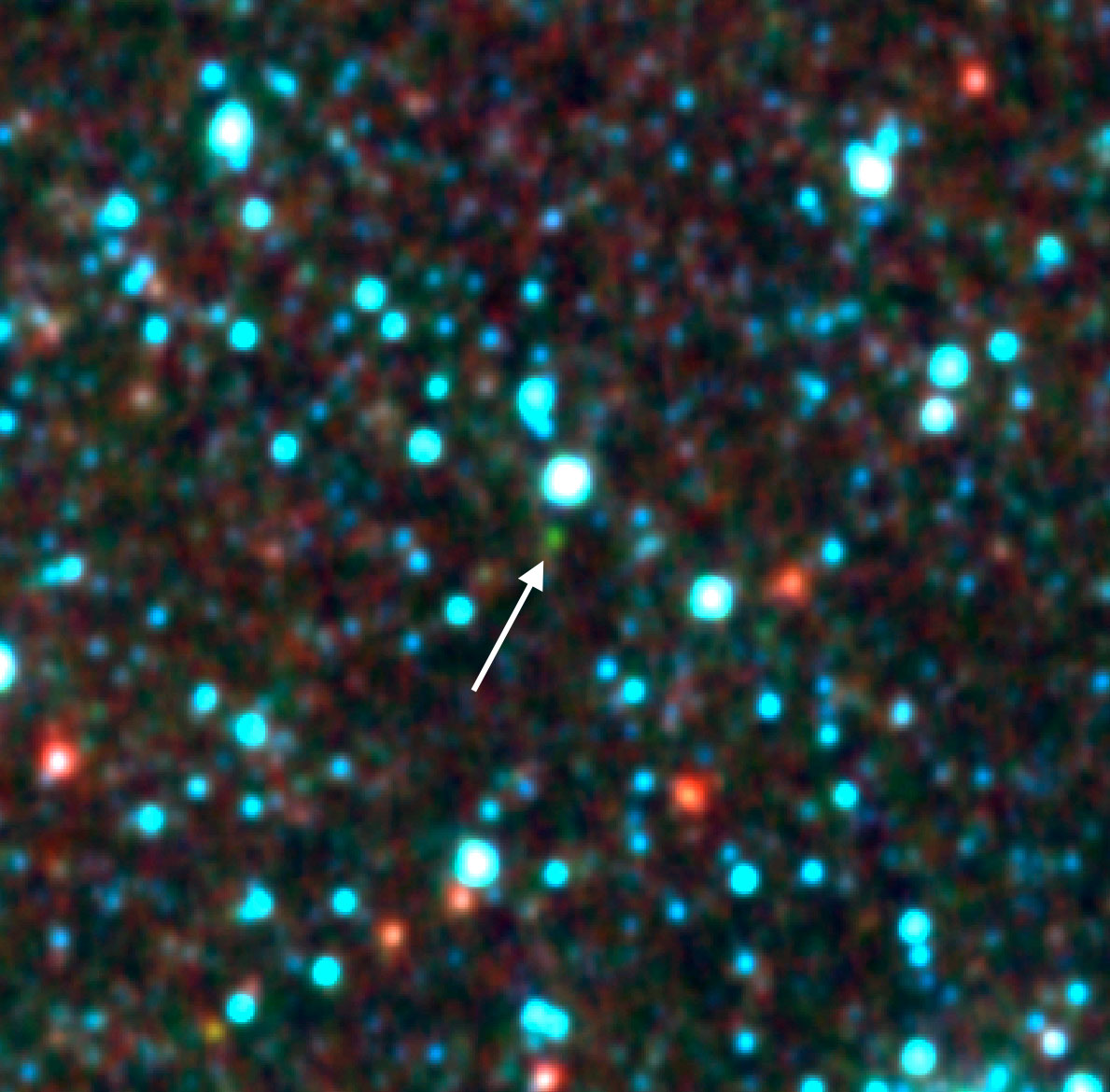

Celestial failure: WISE detected this brown dwarf located about 19 light-years from Earth. Credit: WISE/IRSA.

Becoming a star can be a challenge. But new observations reveal that it's much easier in space than in Hollywood. Only about 14 percent of all aspiring celestial stars fizzle out, researchers report.

In principle, it's easy to deduce how many stars succeed: just compare the number of normal stars with the number of failed stars, also known as brown dwarfs. These flops are born with less than 8 percent of the Sun's mass, so their centers never heat up enough to sustain the nuclear fusion of hydrogen-1, the isotope that powers so-called main-sequence stars like the Sun. Most brown dwarfs do burn hydrogen-2, or deuterium, but it soon runs out, and all nuclear reactions cease. When young, a brown dwarf glows red--chiefly from the heat of its birth--and then cools and fades as it ages. That makes them hard to find--and thus hard to know whether they're rare or as plentiful as full-fledged stars.

Astronomer J. Davy Kirkpatrick of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and colleagues decided to take a look at infrared wavelengths, where the objects emit most of their radiation. The team used NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) spacecraft, launched in late 2009, to detect brown dwarfs near the Sun, some of which have cooled to room temperature. WISE spotted 16 previously unknown brown dwarfs within 26 light-years of Earth. As the astronomers will report in the July 10, 2012, issue of The Astrophysical Journal, comparing the number of brown dwarfs with the number of full-fledged stars suggests that the solar neighborhood has one failed star for every six success stories.

"It was surprising to me," says Kirkpatrick, who had expected to find far more brown dwarfs. If they were more common, one might reside even closer than Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to the Sun. "It's a lot less likely we're going to find any brown dwarf that's that close." The two nearest known brown dwarfs orbit Epsilon Indi, a star 11.8 light-years away, which is nearly three times farther from Earth than Alpha Centauri.

Astronomer Aleks Scholz of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies says the new estimate for the number of brown dwarfs agrees with his team's result from a very different approach: searching star clusters so young their brown dwarfs haven't had time to fade, making them easier to spot. He and other astronomers have found an approximately 1:5 ratio between brown dwarfs and normal stars.

However, astronomer Todd Henry of Georgia State University in Atlanta is critical of the new work's conclusion. "I think it's premature," says Henry, who suspects that many of the brown dwarfs WISE has found are farther away from Earth than claimed. That would mean they are less abundant than the researchers estimated, and Henry says the ratio of brown dwarfs to normal stars could be anywhere between 1:5 and 1:20.

Ken Croswell earned his Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard

University and is the author of The Alchemy of the Heavens and The

Lives of Stars. "An engaging account of the continuing discovery of our Galaxy...wonderful." --Owen Gingerich, The New York Times Book Review. See all reviews of The Alchemy of the Heavens here.

"A stellar picture of what we know or guess about those distant

lights."--Kirkus. See all

reviews of The Lives of Stars here.

| BOOKS | F. A. Q. | ARTICLES | TALKS | ABOUT KEN | DONATE | BEYOND OUR KEN |

|---|